The State Is Organized Plunder | Critical Thinking Is the Only Path to Freedom

LewRockwell.com | George F. Smith

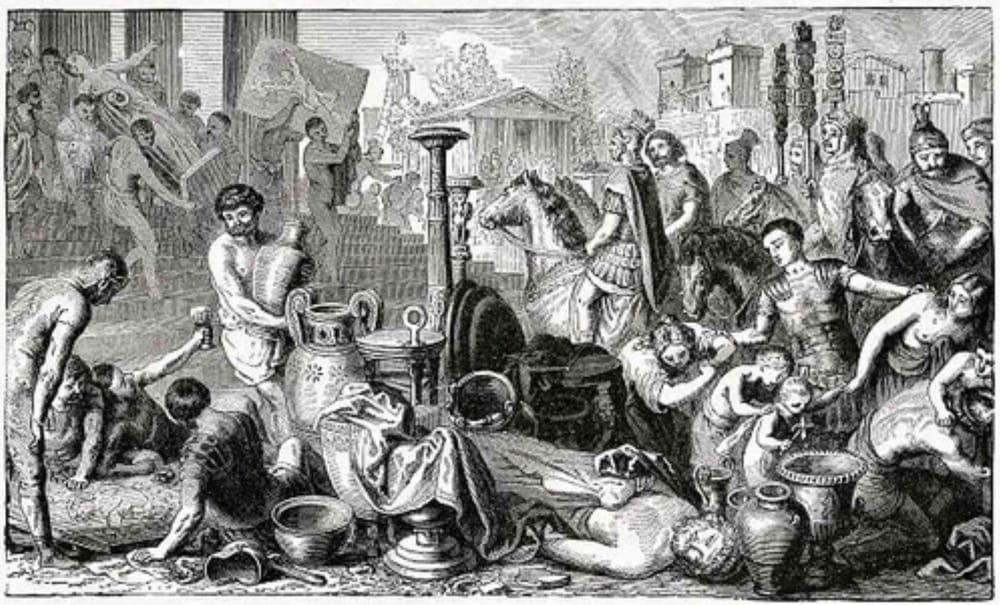

As wise beekeepers leave their bees enough honey to carry them through the winter, so too invading hordes learned long ago that obliterating productive tribes for their wealth is not a long-range solution. Far better to reside among the conquered and make sure they keep the support uninterrupted. And not just support, but glorification of the conquerers for providing protection from other invaders. In a malevolent twist on this arrangement, modern “protection” comes in the form of assaults on other peoples, for which the state has bribed its own youth to carry out the attacks.

There is a great need for people to question the nature of the state. If they do, they’ll find they don’t need the theft of taxation. They don’t need a counterfeiting central bank. They don’t need its false flags. They don’t need its wars of aggression. They don’t need its imposed bureaucracy of economic and social intervention. The state’s non-necessity is an idea in full public view.

The catch is, people have to think about these things. The state goes to great lengths to keep us distracted.

The Greeks and open inquiry

Once upon a time men questioned everything, mostly without fear of punishment. The most famous exception was Socrates, who was charged with corrupting Athenian youth with atheism and forced to drink hemlock. The death sentence was quite possibly the result of him lecturing the jury on its ignorance and incompetence, saying that “after 50 years of submitting the wisest people he could find to questioning, he still hadn’t found anyone with any wisdom at all.” While likely true, his life wasn’t in the hands of truth-seekers.

Greek philosophy seemingly knew no bounds. Is it possible to step into the same river twice? Heraclitus thought you couldn’t. Is the river actually flowing? Parmenides thought it was an illusion. Is nature infinitely divisible? Lucretius argued that it wasn’t, that tiny things called atoms were the basis of existence.

Their inquiries pushed into politics, as well. Thrasymachus, featured in Plato’s Republic, argued that justice is nothing more than the expression of the stronger. Zeno of Citium “envisioned a society without conventional institutions like temples, law courts, or gyms, arguing that wisdom and virtue alone should guide human conduct.” There should be no family, no private property, no money.

When we examine the differences among Classical philosophers we find a steady truth, that the mysteries of the universe and everyday life were open to rational inquiry, even if today some of their ideas are wildly untenable. Aristotle, the last of the great thinkers, left mankind a great gift that was lost to the West for centuries.

The partnership of church and state

Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire under Emperor Theodosius I in 380 CE (with the Edict of Thessalonica). “It was the first secular law to explicitly define religious orthodoxy and authorized punitive measures against dissenters. . . [The decree] commanded that all who followed this faith be called ‘Catholic Christians,’ a term that distinguished them from heretical groups.” But something unknown to common folk slowly developed that became the intellectual groundwork of a better life for their descendants.

As the twelfth century dawned, Europe stood on the cusp of an intellectual awakening so profound that its echoes would reverberate through the halls of history. . . . Natural philosophy was central to this transformative period, a field that emerged as the fulcrum around which all other disciplines began to pivot. . . . the natural world became not merely a creation to be marveled at in its divine artistry but also a puzzle to be solved through the keen application of observation and reason.

Prior to 1100, medieval scholars knew of Aristotle solely as a logician. The rest of his corpus was known only in the Moslem world and Byzantine Empire. During the 12th century Christians, Muslims, and Jews, working together in Toledo, Spain and Palmero, Sicily translated his works into Latin. Once these texts reached the University of Paris, the intellectual capital of Europe, they caused a major disturbance.

In Aristotle’s Children, author Richard E. Rubenstein tells us,

Because of the threat they posed to established modes of thought, Aristotle’s books of “natural philosophy” were originally considered too dangerous to be taught at European universities. Early in the thirteenth century they were banned, and some of their more wild-eyed proponents were burned as heretics. As late as 1277, the Church condemned a number of Aristotelian ideas being taught in the schools, including some propositions espoused by the century’s greatest genius, Thomas Aquinas. In the end, however, the leaders of the Church allowed Christian thinking to be transformed by the new worldview. [My emphasis]

Aristotle’s cosmology at first buttressed the existing social order as it advanced the idea of a hierarchal structure to the universe, with earth at its center. This not only “reinforced the idea of human centrality in God’s plan,” it provided a rational structure to the existing divine-right state.

Aristotle’s manuscripts were treated like scripture in a sense, something to be read and absorbed but not criticized. Later, to be accused of being an Aristotelian was to be accused of treating his ideas as dogma. But crude as some of his pronouncements were, Aristotle himself based his claims on what he saw and deduced from the natural world. His tools were reason and the senses. Together they provided a tentative understanding of reality. Aristotle was not Aristotelian.

This development of critical thinking skills was fundamental to freeing people from oppression. The cultural movement known as Renaissance Humanism that spread across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries, was started by literary elites who “sought to create a citizenry able to speak and write with eloquence and clarity, and thus capable of engaging in the civic life of their communities and persuading others to virtuous and prudent actions.” Following this we saw the Reformation and centuries later, the Enlightenment, that provided the philosophical basis for man’s rights and the Declaration of Independence.

For a Medieval serf to openly question the legitimacy of his rulers was to risk losing his head and eternal damnation, though in practice heresy trials and punishments were aimed more at priests, scholars, or nobles who challenged Church doctrine than at illiterate peasants. The combination of sacral kingship (divinity of the monarch) and ecclesiastical monopoly on learning kept dissent perilous. Aristotle and other thinkers broke the chains of dogma gradually and made inquiry legitimate.

Conclusion

Thinkers who have advanced the conquest theory of the state include Oppenheimer (1908), who likened the state to beekeepers, Nock (1935), and Rothbard (1974). All see the state as organized plunder, not a contract between rulers and ruled. Morally, because of its coercive nature the state has no legitimacy, and practically, it is not only unnecessary but detrimental to human existence.

“Resolve to serve no more,” wrote a youthful Étienne de La Boétie around 1552. He was calling on people to think about their political condition. It’s up to us to follow his counsel.

Image: Source [Plundering Of Corinth Engraving From 1882 Featuring The Plundering Of Corinth By The Romans Under General Lucius Mummius Achaicus.]

Original Article: https://www.lewrockwell.com/2025/10/george-f-smith/critical-thinking-is-the-only-path-to-freedom/

Truth Warriors | Armed With The Truth • United We Stand

Thank you for being one of the individuals in our world that wants the truth. Thank you for reading articles on Truth11.com. Thank you for sharing the truth and for speaking the truth.

Thank you for being a Truth Warrior!.

Truth11.com is an independent media site. Our mission is to arm you with the truth. Please join us in our mission by becoming a monthly subscriber to help us cover costs.

Comments ()